Warren Spector On Life After Mickey, Going 'No Weapons'

Spilling The Glass

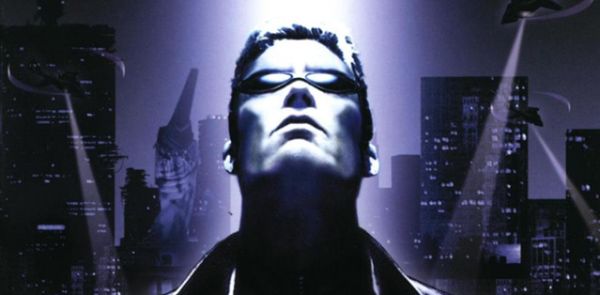

For the first time in ages, Deus Ex director Warren Spector is unemployed. The man who created what's regarded by many as the greatest game of all time isn't cracking any whips, cooking up cyber conspiracies, or teaching cartoon mice to sing. Instead, he's taking some time to both teach and learn, which is what brought him to UC Santa Cruz's recent Interactive Storytelling Symposium. There, he echoed the refrain that's recently become his calling card: take games to new, interesting places, and don't just lean on crutches from film, TV, and the like to do it. It was a call to action - a plea for tomorrow's burgeoning brains to break outside the box and then burn the remains. Do not, however, mistake that for an admission of inaction on Spector's part. Unemployed or not, his gears are churning again, and he's starting to think about his next big move. After his session, Spector and I discussed why he can't simply make another Deus-Ex-esque game, why he really wants to put a “no weapons restriction" on his next project, Kickstarter's popularity among his pioneering peers, Epic Mickey in retrospect, and more.

RPS: When people hear your name, they think Deus Ex. But that hasn't been "you" for quite some time. What, specifically, made you want to leave that side of game development behind?

Spector: I left Ion Storm because it just felt like I didn’t fit at Eidos. Eidos took control of Ion Storm at one point, and they were making games like 25 to Life and On the Mic and Hitman 3 and Crash and Burn. I just didn’t want to make games like that. I was at a point where I thought it would be fun to do my own thing for a while, where I could either go out of business or do the games I wanted to do.

RPS: Since then, you've gone from being the authority on tough guys in trench coats to their most outspoken opponent. But, I mean, are you really over that stuff?

Spector: My geek credentials are in good order, you know? I love fantasy games and I love science fiction. I love real-world near-future kinds of stuff. But I wanted a change of pace. After Ultima Underworld and Ultima VII: Serpent Isle, I was so sick of fantasy. I “never wanted to do another fantasy game” at that point. So I started doing some science fiction stuff, which I liked. After a couple of Deus Ex games, I wanted to do something different again. People expect you to fit in a slot. A square peg only goes in a square hole. But I wanted to do something different.

RPS: Speaking of, um, the opposite of doing something different, a lot of industry pioneers are now launching Kickstarters and going back to their roots. As someone who's fought so hard to push beyond a perceived "box," what's your take on that trend?

Spector: I certainly understand it. I look back on the games I’ve worked on and I have very fond memories of Deus Ex and System Shock and Underworld. Those are an important part of my life. Would I revisit them in the sense of, “Hey, let’s put some pretty graphics on an old game”? No.

Well, OK, if someone gave me the opportunity - I guess it would have to be EA - to go back and take some of the ideas behind an Underworld or a System Shock, I’d have to think pretty seriously about that, for sure.

RPS: During your talk, you said that we don’t really create worlds anymore. Just sets. I think that’s one of the things that a lot of people reviving classics with Kickstarters are trying to bring back: the sheer scope and possibility that came along with smaller productions and budgets.

Spector: Yeah, absolutely. We’ve put so much emphasis on graphics and on amazing sound… We have lost something. I don’t know that it was necessary to lose it, but we have. It’s so much easier to create that feeling that you’re in a world and make a world rich and interactive when you’re dealing with 2D graphics, or really simple 3D graphics. Doing an immersive simulation like we did back in the Ultima Underworld days with modern technology and modern hardware, it would cost $100 million. I really do understand why people are doing it. I’d like to see us try and do it in the context of modern tech and modern hardware. But that’s going to be tough to pull off.

RPS: In terms of bringing back some of that spirit or that experimentation, there’s also the indie scene. But during your talk, you also said you’re not sure if it'll make any significant impact on more mainstream games.

Spector: It’s not really that I’m not sure it can. Maybe I misspoke. It hasn’t so far, and I don’t see any signs that it’s going to. I certainly hope it can. I hope it does start affecting some of the more mainstream games. It just hasn’t yet. And I’m not sure I see the path. I’m not sure I see the way it happens.

One other thing about worlds: I don’t want people to get the wrong impression. I’m probably going to be talking about that quite a bit, actually, for a while now. When people think about worlds, virtual worlds, they think about enormous, fully explorable, Grand Theft Auto, Red Dead Redemption, Skyrim, that stuff. I’ve never done that. I never wanted to do it. Well, that’s not true. Back in the Ultima days, that’s kind of what we did. But around the time of Underworld and System Shock and Deus Ex, I got a lot more interested in really deeply simulated smaller spaces. I’d rather do something that’s an inch wide and a mile deep than something that’s a mile wide and an inch deep. I want to create worlds, but by “worlds” I mean someplace where every object is interactable. The NPCs actually have something to do other than kill you. Every door can be opened and there’s a reason to open them. That’s what I mean by creating world. It’s not about size and scope, it’s about depth and interactivity.

RPS: I found it interesting, during your talk, that someone had a game that did one of your most popular examples. You bring up the water-spilling thing a lot. Spilling water on somebody, having them react to it at all, and then basing their level of infuriation on how much they like you, etc.

Spector: Yeah, yeah.

RPS: And that exists.

Spector: Versu [from Linden Labs], it’s really interesting. Everybody should go and play it. The problem is getting… Not even just that level of interactivity. We need even greater levels of interactivity, and we need it graphically presented. I love words. I have so many books. I have a library, a building that is a library, OK? That’s how much I love books and the printed word. I live with a writer. My wife is a fiction writer. I love it. But to reach a larger audience with games, we have to be able to illustrate what we’re doing. Realtime graphics. As soon as you do realtime graphics, the difficulty and cost of that glass tipping over is huge.

RPS: You may not have noticed this, but you are Warren Spector. That in mind, how does somebody like you - someone with both the desire to make this stuff happen and probably the means to do it on a large scale - approach this issue? Where do you start in terms of introducing more interesting scenarios and subject matters to mainstream games?

Spector: When games cost as much as they do, taking risks is maybe even irresponsible. I have a rule. Well, I have like seven questions I ask myself about a project before I’ll even start it. One of them is, “What’s the one thing in this game that no one in the world has ever seen or done before?” If there isn’t an answer to that, and if I can’t answer all seven of those questions, I won’t even start the project. It’s dead before it gets started.

But that’s important. I’ve never worked on a game that didn’t have something no one had ever seen before. People may not notice it, people may not see it, but it’s there. The way to do that is to do it, you know? Your publisher is going to give you money. You’re going to get money from somewhere. Take a little bit of it and do something that’s new and different. You can do that in the context of fill-in-the-game-name-of-your-choice. You can always do one new thing. Come on.

RPS: Out of curiosity, what was that one thing in Epic Mickey?

Spector: In Epic Mickey, it was a couple of things. It was the dynamically changeable environment. As far as I know there had never been and still has never been another game where you can dynamically remove and restore parts of the terrain, characters, objects, that sort of thing.

Not that I want to get into this – please, let’s not get into this – but the fact we let you dynamically change the terrain in Epic Mickey was largely responsible for a lot of the camera issues we had. The fact is, even people who worked on game cameras before and know how to do them inside out, have never tried to do it in the context of a world where there might be a wall here, or there might not. There might be a part of a wall here, or there might not. The camera might be doing just the right thing until Mickey goes and erases a wall, goes through it, and then paints in a little part of it. What does the camera do there? That was the big thing we did.

There were a couple of other things that were pretty darn new. And certainly just the whole choice and consequence thing that’s part of every game I do. No one had ever done that or has ever done that in the context of a hybrid action-adventure platform game. A lot of people on my team wanted… I mean, we fought all the time over this. “Why don’t we just do a platform game? Let’s just do a platform game. Let’s just do a platform game. We can tune a platform game really well. Let’s just do that.” No. That’s a solved problem. It’s better to fail gloriously than it is to succeed at something mediocre.

RPS: And obviously you don’t think those games were failures.

Spector: No, not at any level.

RPS: A lot of people didn’t react quite as well to them.

Spector: Core gamers didn’t, yeah.

RPS: Why do you think so many people didn’t see eye-to-eye with you on your vision for those games?

Spector: OK, to be clear, a lot more people saw eye-to-eye with the vision than didn’t. Mickey 1 is the best-selling game I’ve ever worked on in my life. Mickey 2 is the second-best-selling game I’ve ever worked on in my life. I have more fan mail and more heartfelt fan mail from more people of different genders and ages than I’ve received for every other game I’ve worked on combined. Disney fans loved the games, and there are a lot more Disney fans than you might think. So on that level, from a commercial standpoint, I don’t consider them failures.

From an acceptance standpoint, normal people got that game in a way that core gamers didn’t. Why is that? Who the heck knows? I’m totally speculating, but my assumption is, “Oh my God, it’s Mickey Mouse.” That’s one problem. Another problem is, “What do you mean you’re not making a game about a guy wearing a trench coat and sunglasses and wearing a gun? Go back and make the kind of games you always used to make.” I wanted to do something with a different kind of tone, a different look graphically. I wanted to try making a game with different kinds of mechanics – platforming and that Zelda-like action-adventure element. I’d never done that before. If people liked it, great. If they didn’t, I’m fine with that. I got to do it.

And like I said, they sold really well. I don’t want to exploit some of the fan mail I’ve gotten, but I could reduce you to tears right now by telling you about a lot of the fan mail I got, a lot of the fan art that I got, and a lot of the custom plush toys that people made of the characters. I mean, it’s just amazing. The response to the games was fantastic, except from Deus Ex fans, who I know are mad at me [laughs].

RPS: During your talk, you said that you’re still interested in working on, as you define them, “part roller coaster, part sandbox” games - ala Deus Ex or Epic Mickey. But also you said you feel like you're sort of hitting the point where they aren't necessarily interesting to you anymore.

Spector: I wouldn’t say they’re not interesting to me. I’m frustrated that, almost 20 years after I started making games like that, that’s still the best I can think of? I honestly don’t know what I’m going to be doing now. I’m really enjoying taking some time off for the first time in my life. But I assume that at some point I’m going to start doing something and making games. I doubt I’m going to end up working for a big company.

But what I want to do, in whatever I do next, is I’d like to start pushing a little bit, seeing if there are other structures, seeing if we can do things with AI that we haven’t done before. I want to take interactive storytelling to another level. I don’t know how to do it, so I need to construct a team of people who are really psyched about that, who are really smart, and who I don’t have to fight with about choice and consequence. I need people who are willing to do the work to be offering people the opportunity to interact with a world in the way they want and live with the consequences of those choices.

RPS: Speaking of AI, have you had the chance to play BioShock Infinite?

Spector: Yeah.

RPS: What'd you think of Elizabeth from an AI perspective? I mean, she's being cited as one of the best non-enemy AIs we've seen in quite some time, but she was also kind of generally awkward and I could never stop wondering why the bad guys didn't just kidnap her mid-battle.

Spector: BioShock Infinite… I mean this as a total compliment, by the way. Please do not mischaracterize this. I think it’s absolutely the state of the art currently in terms of well-disguised roller-coaster games. It tells a phenomenal story. It has pretty robust companion AI. It’s got an absolutely wonderful, unique world with a unique color palette. I think it’s a really, really excellently implemented version of that kind of game. Probably the best we have. I think there’s still plenty more we can do and need to do on the AI front. But I’m glad to see people doing anything at this point that doesn’t involve flanking tactics and getting stuck on geometry [laughs].

RPS: For a lot of people, though, I think it still fell apart once combat entered the picture. For whatever you might end up working on next, have you given any thought to the idea of removing guns entirely?

Spector: I almost hesitate to say this, because I don’t know if it’ll actually happen, but I can’t tell you how desperately I want to impose the “no weapons” restriction on whatever I do now. Just to force myself and the team to solve a lot of tough problems. Guns and swords, they’re such crutches for us. They’re so easy for us to do. Unless we force ourselves to do the hard things, I’m not sure we ever will. I don’t know. I may not actually do that. I may end up doing a game where you get to shoot lots of people. Who knows? But I’d very much like to impose that constraint on things. We’ll see.

RPS: Thank you for your time.